Benjamin Britten: Canticle III: Still falls the Rain

This academic analysis of the work was originally written to accompany a lecture-recital.

Canticle III: Still falls the Rain, op. 55

Benjamin Britten (1913-1976)

text by Edith Sitwell (1887-1964)

tenor, horn, piano

Composed 1954. First performance: January 28, 1955, Mewton-Wood Memorial Concert, Wigmore Hall, London. Peter Pears, tenor; Dennis Brain, horn; Benjamin Britten, piano.

In 1954 Benjamin Britten was asked to compose a piece in memory of Noel Mewton-Wood, the Australian pianist who had died recently at age thirty-one. Mewton-Wood was a close associate of Britten’s; in addition to occasionally accompanying Peter Pears and performing at the Aldeburgh Festival, he premiered the revised version of Britten’s piano concerto in 1946. Despair after the death of his partner had driven Mewton-Wood to kill himself, and Britten was shaken by the news. In her diary entry for 7 December 1953, Imogen Holst wrote, “He was looking grey and worried, and talked of the terrifyingly small gap between madness and non-madness, and said why was it that the people one really liked found life so difficult.”

Throughout the earlier part of Britten’s career, his work as a songwriter focused on the composition of tightly unified cycles. These cycles generally set either an anthology of poems focusing on a single theme, such as Our Hunting Fathers and the Serenade, or a collection of verses by a single poet, generally also on a single theme or mood, such as On This Island, the Seven Sonnets of Michelangelo, and The Holy Sonnets of John Donne. Within these cycles, there are few individual songs which retain their effectiveness divorced from the context of the larger work. In the late 1940s, however, Britten began occasionally to set poems that, due to their length and complexity, were better-suited to stand on their own. He called these settings “canticles,” a description meant to acknowledge not just the religious nature of the texts (many of his other songs had been religious in nature), but also an intensity of spiritual tone requiring more substantial musical form.

Faced with the prospect of selecting a text for the Mewton-Wood commission, Britten, in an uncharacteristic move, chose one by a living poet — “Still falls the Rain,” from the British poet Edith Sitwell’s The Canticle of the Rose: Selected Poems. The poem, given the subheading “The Raids, 1940. Night and Dawn,” was written in response to the Second World War, but Britten explained to Edith Sitwell that in her poem’s “courage & light seen through horror & darkness,” he found “something very right for the poor boy.” It is quite likely that Britten had been introduced to the poem as early as 1941, when it was published in the Times Literary Supplement. Britten wrote that he had been “deeply moved” by the poem “& felt at last that one could get away from the immediate impacts of the war & write about it.”

Edith Sitwell’s poem is structured as seven free-verse stanzas, the first six of which begin with the line “Still falls the Rain.” The poem draws on the Passion scene for its imagery, with each verse more intensely portraying the agony of the crucifixion, presented as a parallel for the German bombing of London. The final stanza, a mere three lines long, gently transforms this overwhelming despair into quiet optimism — “courage & light seen through horror & darkness.” Despite its use of free verse, the tone and imagery in the poem recall the poetry of Jonson, Donne, Marlowe, and other Elizabethan poets. The poem climaxes, in fact, with a quote from Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus. This was language with which Britten was intimately familiar; he had previously set John Donne (The Holy Sonnets of John Donne, op. 35 [1945]), Francis Quarles (Canticle I: My beloved is mine, op. 40 [1947]), and realized a number of Henry Purcell’s works, including several of the Divine Hymns from Harmonia Sacra, which served as models for the canticles.

In structuring this canticle, Britten took his cue from the text itself. Responding to the six major free-verse stanzas, he devised a series of six rhythmically-free recitatives (“verses”), each of which begins with the same setting of the opening phrase:

Interspersed between these verses is a series of interludes in the form of a theme and variations:

| Theme | Verse 1 |

|---|---|

| Slow and distant | (“Dark as the world of man…”) |

| Variation I | Verse II |

| Gently moving | (“With a sound like the pulse...”) |

| Variation II | Verse III |

| Moderately quick | (“In the Field of Blood...”) |

| Variation III | Verse IV |

| Lively | (“At the feet of the Starved Man…”) |

| Variation IV | Verse V |

| Quick and agitated | (“Still falls the Blood …”) |

| Variation V | Verse VI |

| March-like | (“Then— O Ile leape up to my God…”) |

| Variation VI | |

| Slowly, as at the start | (“Then sounds the voice”) |

Each verse draws its supporting texture and motivic materials from the preceding interlude. Further clarifying the structure, Britten wrote the piece for tenor, horn, and piano. Throughout the canticle, the voice and horn are heard separately: the voice sings the verses, while the horn plays the interludes. This holds true until Variation VI, when, for the first time, the horn and voice are heard together, without piano, in the final stanza of the poem.

This structure is identical to that of The Turn of the Screw, which Britten had completed earlier in 1954. This opera is structured as a series of sixteen scenes, with a theme and variations acting as interludes between scenes. Each interlude provides the musical material for the subsequent scene. Canticle III is an even further-concentrated working-out of this formal design, with the verses acting as analogs to the scenes of the opera. Britten was fully aware of the close relationship between the opera and the canticle; a few months after the premiere, he told Sitwell that The Turn of the Screw and Canticle III brought him to “the threshold of a new musical world.”

The horn and piano begin the canticle with a statement of the theme. Melodically, the theme consists of three gestures. The first is a gesture rising up a whole tone scale a tritone from B-flat to E before dropping back a perfect fourth to B, one half step higher than it began. The second gesture begins a major sixth higher than the first, on G, and inverts the initial gesture. The third gesture sequences on this motive, alternating between the prime form and its inversion, before cadencing once more on B-flat. This cadence subverts the natural expectation we have of the motive (that is, a final drop of a perfect fourth to D-sharp) by continuing one step further on the whole tone scale to A-sharp, displaced by one octave and enharmonically spelled as B-flat.

Many theorists, excited by the discovery that the theme makes use of all twelve pitches, have attempted to ascribe some kind of serial procedure to this theme. However, there is no convincing evidence of any such procedure; most theorists who attempt this approach either allude to serial processes in passing as though they were obvious or attempt briefly to find evidence of serialism before tacitly conceding defeat and moving on to other aspects of the piece. The truly significant feature of the theme lies in its manipulation of the initial motive. The appearance of all twelve pitches in the theme is due, not to any awkward attempt at tone-row construction and serial processes, but to Britten’s use of two whole-tone fragments a semitone apart as germ material.

The most prominent chord type throughout the theme is that of a perfect fourth stacked atop a major second (for example, G-flat—A-flat —D-flat in measure one). This unifies the harmony with the whole tones and perfect fourths of the melody. Harmonically, the theme consists of a series of diatonic collections which use the whole-tone fragments as common-tone pivot gestures on which to modulate. The first three measures, for example, make use of the five-flat diatonic collection (“D-flat major”), with a chromatically inflected G in measure three. In measure four, the piano drops down to an octave E, anticipating the high point of the horn as it ascends the scale fragment. Measures five through seven then make use of the one-sharp collection. The horn melody is used once again to modulate to the four-sharp collection (G-flat is redefined as F-sharp) in measure nine, and then to the one-flat collection in measure eleven. At this point, the melody begins its sequence to the final cadence. As previously mentioned, this cadence is achieved melodically by extending measure thirteen’s whole-tone motive one note further to return to the initial B-flat. The subtle shift from development into denouement is reinforced in the harmony by the use of an F dominant ninth chord here, providing a strong dominant preparation for the horn’s arrival on the tonic (B-flat). Britten avoids stumbling into banality by implying, rather than explicitly stating, the shift to the tonic; the arrival on B-flat is stated by horn alone, rather than being reinforced by a B-flat chord or chord tones in the piano.

Following this cadence is a coda in which the piano’s rising chord progression recalls the opening three measures of the theme:

Britten uses this cadence to transition from the harmonic ambiguities of the interludes to the B-flat clarity which characterizes the harmonic material of the verses.

On a basic level, the variations function by expanding and contracting the whole-tone fragments of the theme:

| Whole Tones Become: | Basic Meter | Basic Dynamic | Texture | Length | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theme | n/a | 5/4 | pp - mf – pp | theme stated in horn over rising chords in piano | 16 bars (1’29”) |

| Variation I | thirds | 2/4 (6/8) | pp - mf – pp | theme (expanded to thirds) in horn over 6/8 pulsing piano chords | 17 bars (30”) |

| Variation II | semitones | 4/4 | pp - f – pp | chromatic sixteenth notes in horn over piano tremolos | 12 bars (25”) |

| Variation III | fourths | 4/4 | pp – ff | three part invention – piano imitating staccato rising and falling fourths in horn | 16 bars (25”) |

| Variation IV | unisons | 5/4 | f | brassy repeated sixteenth note quintuplets in horn over piano tremolos | 10 bars (31”) |

| Variation V | fifths | 4/4 | ff | March – dotted eighth-sixteenth feel in horn and piano; emphasis on fifths | 17 bars (37”) |

| Variation VI | B-flat major | 5/4 | p | horn and voice in first species counterpoint; voice sings horn part inverted on G. Smooth, even scalar texture | 11 bars (1’24”) |

Thus, in each variation, the contour of the melody remains constant. As in most of Britten’s music, rhythm as a musical element is important only insofar as it helps to generate the character of each section. There is no evidence of systematic rhythmic transformation within the variations, and, in fact, a glance at the theme suggests that he intentionally avoided infusing it with any distinctive rhythmic profile so as to allow for greater flexibility in later variations.

The accompaniment of each verse evolves from the preceding interlude. The musical material and mood of each variation often foreshadow the text which is about to be sung. Thus, the variations, far from being independent interludes between stanzas, are inextricably bound up with the text itself, often engaging in a kind of preemptive word painting:

| Significant Words/Textual Features | Reflection In Music | |

|---|---|---|

| Verse I | “nineteen hundred and forty nails” | foreshadowing of pulsing eighth notes of next variation/verse |

| Verse II | “pulse of the heart,” “hammer-beat,” “sound of the impious feet” | pulsing eighth notes in 6/8 |

| “On the tomb” elides with next stanza; this is the only point in the poem in which “Still falls the Rain” does not begin a stanza | “On the tomb” overlaps with the beginning of Var. II and, thus, the texture of Verse III; this is the only point in the piece (before Var. VI) in which the voice and horn overlap | |

| Verse III | “Field of Blood,” “Nurtures its greed, that worm” | use of chromatic scale to suggest worm imagery |

| Verse IV | “Christ that each day…” | use of hymn/carol-like texture (and modulation to E tonal center from Bb; cf. the rise from Bb to E in the theme motive) at this point to set off prayer from rest of text |

| “have mercy on us” | lengthy diatonic (white-note) vocal melisma starting on highest sung pitch in canticle | |

| Verse V | “Still falls the Blood” | “Still falls the Rain” refrain motive repeated minor third higher at forte dynamic (as opposed to piano dynamic of “Still falls the Rain” statement) |

| “the blind and weeping bear whom the keepers beat” | set off by sudden return to recit texture after passage of agitated staccato sixteenth notes | |

| “the hunted hare” | hunting horn gestures immediately begin next variation | |

| Verse VI | “O Ile leape up to my God: who pulls me doune…” | declaimed fortissimo using same dotted rhythm as Variation V |

| Variation VI | “ ‘Still do I love, still shed my innocent light, my Blood, for thee.’ ” | intoned peacefully on single pitch (Bb) in unison with horn |

| 3 lines in final stanza | 3 gestures in theme |

For example, Variation I features an accompaniment figure of pulsing staccato eighth notes in 6/8 (which had, in turn, been foreshadowed slightly in Verse I in the setting of the words “the nineteen hundred and forty nails”— see the example below). This texture appears in the piano part in Verse II as musical illustration of the “pulse of the heart that is changed to the / hammer-beat…”; three times during the verse (after “pulse of the heart,” “hammer-beat,” and “sound of the impious feet”) the piano states a string of six staccato eighth notes marked as “in prior tempo.”

Much of the tension in Canticle III derives from the contrast between the interludes and the verses. This is not achieved through obvious shifts in texture or character, but through the contrast between the harmonic ambiguities of the interludes and the insistent B-flat tonal clarity of the verses. The theme itself is tonally ambiguous. Any tonality it has is only established with the final cadence on B-flat, and even that is seen only in retrospect after hearing the verse. The first verse, on the other hand, is anchored solidly on Bb. Thus Britten begins by establishing a conflict between tonality and atonality. Broadly speaking, the piece is a process of reconciliation between these extremes— the verses slowly loosen their grip on B-flat, while the variations grow more tonal (though not without a brief relapse in Variation IV), eventually meeting in the text of the final stanza and achieving unity in Variation VI.

As we’ve seen, the theme is introduced as tonally ambiguous. The only accompaniment in this first verse is an open-fifth chord on B-flat which punctuates the vocal line. Only once does it move— up a semitone to an open-fifth chord on B at “the nineteen hundred and forty nails,” emphasizing the new motive in the voice, which will come into play in the next variation:

The vocal line itself focuses strongly on E-flat, but this comes across as a kind of suspension attempting, but failing, to resolve itself.

The first variation takes up the pulsing vocal motive from Verse I as a pulsing eighth note rhythmic accompaniment in 6/8. The horn states the theme over this figure, its tones expanded now to thirds. The harmony is altered to accommodate the varied melody, but the basic harmonic structure remains the same. For example, the first three measures exhibit a shift in the bass line from G-flat to B. This parallels the shift between the opening low Gb of the theme and the horn’s B in the fifth measure, following the first statement of the germ motive:

The harmony rises to an open-fifth chord on F-sharp with a B in the bass at the end of the horn’s second statement (measure six of the variation). A glance at the theme will show a similar harmonic sonority in measure nine, the parallel spot at the end of the horn’s second gesture. Verse II adopts the pulsing eighth notes of Variation I as an accompaniment figure. The semitone rise seen in Verse I is repeated here, but this time, it goes one semitone further, to C, before returning to B-flat at the beginning of Variation II:

At this point, we encounter a subtle example of Britten’s attention to detail in deriving the canticle’s form from the structure of the poem. The transition between the second stanza and the third stanza is the only place (with the obvious exception of the last stanza) in the poem in which a stanza does not visually begin with “Still falls the Rain.” Rather, Sitwell chooses to elide the end of the previous stanza onto the beginning of the next stanza. Reflecting this subtle shift in structure, this is the only point in the canticle in which a verse spills over into a variation. By overlapping the vocal line “On the Tomb” with the beginning of the horn line in Variation II, an elision is created between the end of Verse II and the beginning of Variation II and, thus, the beginning of Verse III.

Variation II contracts the whole tones of the theme into semitones, retaining, as always, the basic contour of the theme. Harmonically, the variation still begins with the G-flat—B-flat dyad and moves to an F-sharp sonority (measure six of the variation) before sliding back into the cadential figure. Verse III picks up on the chromatic lines of the variation, using them to illustrate the words “blood,” “breed,” “nurtures,” and “worm.” The accompaniment exhibits the sixteenth note tremolo qualities of the preceding variation. Harmonically, the verse strays even farther, reaching D-flat before settling back down into B-flat.

Variation III is a “lively” (Britten’s tempo marking) three-part invention between horn and piano in which the melody’s whole-tones have been expanded into fourths. The contrapuntal nature of this variation blurs perception of harmonic material, but the opening G-flat—B-flat dyad is still clearly audible, as is the return to this sonority and resulting cadential figure (measure twelve of the variation). Verse IV retains the staccato eighth note fourths as punctuation to the vocal line. Here, for the first time, the verse breaks free entirely of its B-flat anchor, leaping to an E minor chorale texture for the lines “Christ that each day, each night, nails there, have mercy on us…” This is the only point in the canticle in which Britten allows himself to indulge in archaism, despite the temptation to do so with such a suggestive text. He sets these lines in a manner reminiscent of hymns or Renaissance English carols, with a kind of Lombard rhythm in 6/8 over an accompaniment of open-fifth chords moving in parallel motion. The word “mercy” is the longest melisma in the piece, beginning on the highest sung note in the piece. These elements strongly emphasize the poet’s prayerful petition. Eventually, however, even the E minor chorale returns us to the familiar B-flat open-fifth sonority.

Thus far, the variations have exhibited a subtle shift towards more tonal material. Variation IV breaks from this trend. The melody is reduced to a mere six pitches, approximating the contours of the opening notes of each of the principal gestures of the theme; the whole-tones of the theme have been, in effect, reduced to unisons. The harmony grows highly dissonant, with chords featuring a high number of seconds. For the only time in the canticle, the G-flat—B-flat dyad is not present as a structural point, and the return to the cadential figure in the seventh measure is audible due solely to gesture; the pitches only gradually become apparent. The subsequent verse breaks free of its B-flat tonal anchor almost immediately, assuming the “agitated” rapidly-repeated notes of the variation. This stanza contains some of the most disturbing imagery in the poem— lines such as “That last faint spark / In the self-murdered heart” are particularly poignant considering the occasion of the canticle’s composition. By this point, the distinction between verse and variation material has grown slim; it is only on the last note of the verse that the accompaniment finally returns to its pure B-flat open-fifth sonority.

Taking its cue from “the hunted hare” in the last line of the previous verse, Variation V features a hunting horn march in which the whole-tones of the theme expand to fifths. This variation revives the previously-established trend towards tonality, and the familiar harmonic structure points— the G-flat—B-flat dyad, the F-sharp sonority, the cadential coda figure— return. In addition, the expansion of the theme to fifths results in a circle-of-fifths motion which begins to imply tonality more heavily. Bars ten through thirteen display a final climactic gesture before the overall climax of the piece in the following verse, climbing to the horn’s highest note in the canticle before plummeting a beat later to its lowest—and loudest— note. Verse VI begins firmly anchored on B-flat, although the G-flat—B-flat sonority of the variation has crept into the bass here. The dramatic gesture ending the prior variation carries over into the climactic Marlowe quote (“O Ile leape up to my God…”), which is set off from the rest of the text by being declaimed fortissimo in the dotted rhythms of Variation V. After this climax, the B-flat quietly returns. The slow chromatic rise from B-flat seen in the other verses reaches its highest point here, reaching E-flat, and thus coming into harmonic agreement with the persistent G-flat—B-flat figure in the bass. By this point, verse and variation have become inseparable; the verse has assumed the harmonic materials of the variations.

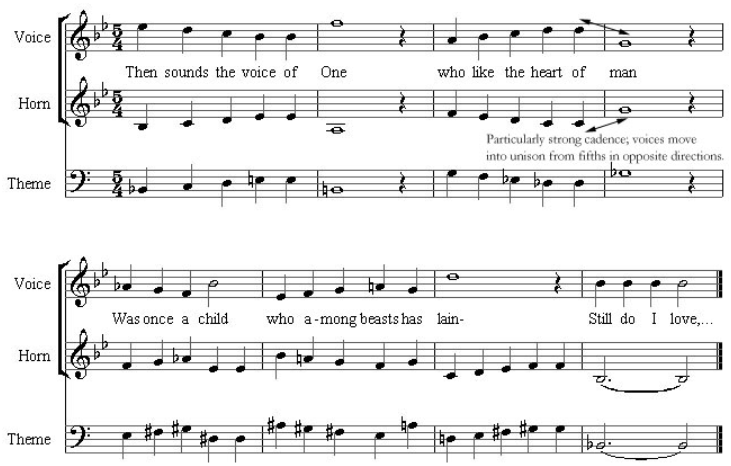

In Variation VI, the shift to tonality in the theme is complete. For the first time, horn and voice join together, without piano— the horn fitting the theme into a B-flat major tonality while the voice sings the same line inverted across G:

It is here that Sitwell transforms the despair of the previous stanzas into hope, and it is here that Britten reconciles the conflicting harmonic systems he set in motion at the beginning of the piece. The whole-tone harmonic vagaries of the theme have become simple diatonicism, and the three gestures of the theme now clearly correspond to the three final lines of the poem; Britten has brought “courage & light” from “horror & darkness.” The horn and voice cadence in unison on B-flat, singing together as the voice of God, reaffirming His love, while the piano quietly restates the cadential figure from the theme’s coda, slightly extended and in octaves.

In Canticle III: “Still falls the Rain,” Britten worked to ensure that every element is unified and integrated into the piece as a whole. Each element relies on every other element in the piece; musical material and structure are derived from the text, and the text, in turn, is foreshadowed and anticipated by the music. The tension and drama derive from the process of integrating the seemingly disparate materials of the two alternating sections— verse and variation— into a unified sound. As musicologist Peter Evans observed, the genius of the piece lies in the fact that “the music under such ponderous discussion is in fact of a lucidity bordering on the transparent;” the canticle stands as a prime example of the “adaptation of abstract compositional procedures to specifically expressive ends.”

Copyright © 2003 Chris Myers. All rights reserved. Unauthorized distribution or reproduction prohibited.